Fell Ponies and Water

/CHRISTINE ROBINSON'S PONIES IN THE SOLWAY FIRTH AT HIGH TIDE. COURTESY CHRISTINE ROBINSON

On an exceptionally high tide in the Solway Firth in the north of England (and south of Scotland), Christine Robinson released her Fell Ponies into the tidelands to see what they would do. Each of them behaved differently, but they all ventured into the water. “The reaction of Fitz View Henrietta, Harthouse Honey and Townend Jasmine to today's high tide was a combination of not bothered and let's play in the water! Henri went in first, but not too deep, then Honey just waded past and started pawing and sloshing the water round. They are crackers! It was heaving it down and blowing a gale, and they had dry ground to stand on but chose to play instead!”

I loved a comment from a fellow Fell Pony enthusiast in reaction to Christine’s photos. “Who needs Koniks?!” Koniks are an imported breed being used for conservation grazing in marshy areas in the homeland of Fell Ponies. While Fells aren’t historically associated with marshland grazing, it’s clear they are amenable to it! And certainly they should be considered whenever conservation grazers in marshland in their homeland are needed.

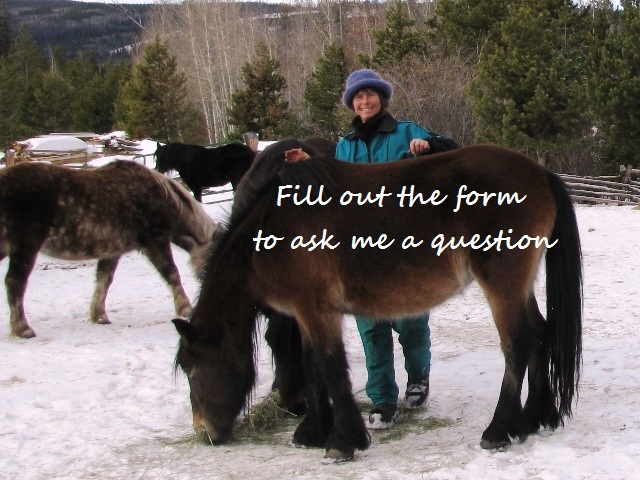

I personally have never seen a Fell unwilling to cross water. One summer when we lived in Colorado, I saw mine standing in the river running through the pasture much more than in the past. I don’t know if it was the particular herd of ponies I had at the time or something else. Two of the four mares were born there and had been crossing that river their entire lives.

In the 1996 Fell Pony Society Spring Newsletter, there is a photograph of six mounted Fell Ponies belly-deep in water. Liz Whitely wrote, “Swimming has been the highlight of the last two years’ [annual trek to the Breed Show.] Makeshift bridles are made and swimming costumes donned (by the riders!) and in we go. The water last year was wonderfully warm and the ponies really loved it – and it makes their coats so soft. When they’re not swimming they often stand and paw the water making a fantastic splash.” (1)

The most dramatic story I’ve heard about a Fell Pony and water was told about Jonty Wilson and his pony Edenview Moonstroller. “One day in March 1976, Jonty was out driving Edenview Moonstroller hitched to a four wheeled flat cart. When he came to a place called ‘Beck Foot,’ …the old road was blocked, but Jonty surmised that if he crossed the river to the field beyond he could then cut back onto the lane, and thereby join his original route. Stroller went so far into the water and then stopped. Jonty asked him to go on, as he thought that he just did not want to go any further. Stroller stepped forward, as he had been told to do, and in doing so stepped off a ledge into some 16 feet of water… Out of his depth, Stroller swam to the opposite side of the river, and despite plunging at the riverbank, it was far too steep for him to be able to climb out. So Stroller turned and swam back to where he had first entered the river, pulling himself, the cart and Jonty to safety. Even if he had been able to swim, which he couldn’t, Jonty feels that if he had not kept hold of the reins he would have been swept away and besides he had on his thick topcoat and his wool lined wellingtons which were enough to drag him under when wet. Jonty emerged soaked to the skin, and although his whip and the coat he was sitting on were both gone, he still had his cigarette in his mouth!” (2) Stroller was born on the day astronauts first walked on the moon, so perhaps he had good water karma from that momentous moon-day!

Whitley, Liz. Fell Pony Magazine, Spring 1996, p. 23.

Wilson, Jonty. “Stroller Saves Jonty Wilson’s Life,” Fell Pony Society Spring Newsletter 2001, Volume 3, p. 48.