Importance of Fell Ponies

/A fell-bred pony leads the herd, the late Sleddale Rose Beauty

This is section 2 of Part 2 of A Fells on the Fells Action Plan -Draft.

The purpose of this section is to describe why Fell Ponies matter, what a Fell Pony on the fell is, why Fell Ponies on the fell matter and how Fell Ponies on the fell fit within the breed.

Fell Ponies are genetically distinct from other breeds.

Fell Ponies are second only to Exmoors in the purity of our genetics. Click here to read more.

Fell Ponies are classed as a rare breed.

Click here to read about the Fell Pony according to the Rare Breeds Survival Trust.

Click here for a detailed discussion of the Fell Pony as a rare breed.

The Fell Pony is named after its native terrain for a reason.

Many characteristics of the breed are derived from centuries of living in the fell environment of northern England. Click here to read more.

There are lots of different words used to describe where Fell Ponies live on vast open land with significant elevation change and with minimal human intervention. Click here to read more.

Fell Ponies on the fell are not believed to be genetically distinct from other Fell Ponies.

See section 4a of David Anthony Murray’s 2013 research (click here).

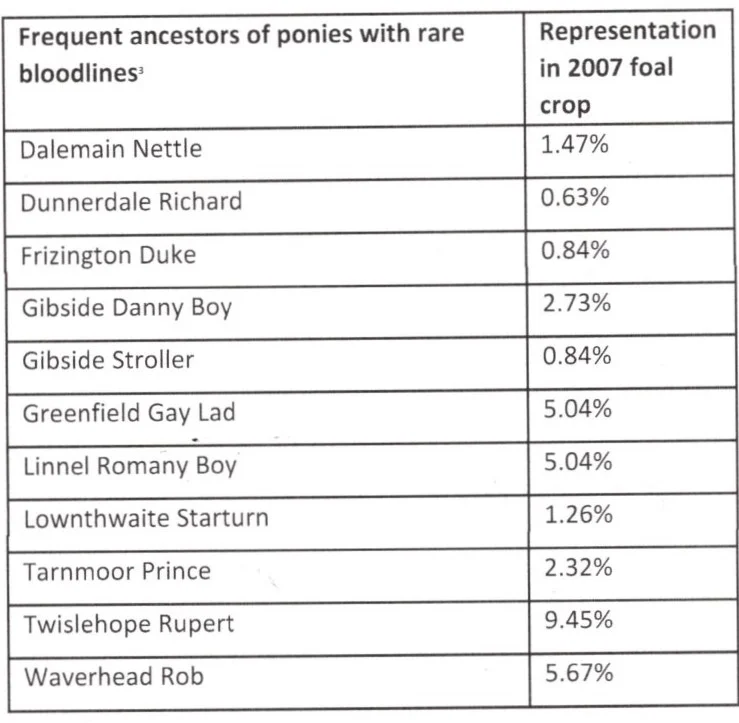

A 2007 study of rare bloodlines indicated that most of the rare bloodlines in the breed are outside the upland herds. Click here to read more.

Another reason that Fells on the fells are not genetically distinct is described in section 5(2) below – because non-fell breeders must return to fell herds to retain type.

Since Fell Ponies cannot easily be returned to the fell once they have lived elsewhere, it is likely, then, that Fell Ponies on the fell do have some characteristics that ponies raised elsewhere do not.

Breeders away from the fells often find it necessary to return to fell-bred herds to retain type. Click here to read more.

Being hefted is one difference between fell-based ponies and ponies living elsewhere (click here to read more about research related to hefting and Fell Ponies.)

It is possible Fell Ponies on the fell have different gut microbiomes than Fell Ponies raised elsewhere. Click here to read more.

While it is not often done, there is some hope for returning ponies to the fells. To read more, click here.

Ponies from upland herds are often considered truer to type than ponies bred elsewhere and are therefore important to the Fell Pony breed’s continuity. Click here for a discussion.

While foals born into upland herds have been increasing in number, research indicates that the proportion of fell-bred foals to the total number of registered foals is falling, a troublesome trend. Click here to read the research findings.

The Fell Pony breed deserves recognition for its uniqueness. Its status as a rare breed also makes it worthy of conservation efforts. Fell/upland-bred ponies within the breed play a special role in preserving the breed’s type. They too, then, are deserving of recognition and conservation. That the proportion of fell-bred ponies is dropping in the breed should be a concern to all breed stewards.